I took poetry and writing for my last course at SFU. I am not a poet, but I did over the course of the course learn much about writing in new forms, new ways to communicate, ways that were more open to interpretation, more visceral, more nuanced and, more engaging for the reader. This is the final paper.

First Stage. The Camino de Santiago, 800 kilometres.

St. Jean Pied du Port, France September 16, 2013

The Camino de Santiago, the Way, is a famous Christian pilgrimage. Folklore says the headless body of Saint James was miraculously found by a shepherd, guided by a star, in the 9th century, somehow mysteriously transported there from the Holy Land centuries before. Sound familiar? Santiago Cathedral, the venerated mausoleum of Saint James’ body, became a pilgrim destination. These days, Popes walk back the dubious myth of Saint James’ miraculous discovery, the story defies logic, geography and history. Pilgrims still come; 250,000 a year.

Departure – September 17, 2013

The jumping off point is Saint Jean Pied du Port, on the French edge of the Pyrenees. A night of no sleep – nervous, manic energy, anxiety, fear of failure, pack/repack, fidget and fret.

The first day is a test of determination, training, desire and grit – a hard 25 kilometre slog over the Roncevalles Pass into Spain. Rain, fog, wind, mud; a slap in the face, no extra charge.

Near the pass, a brass plaque signifies the battle, mythologized in the Song of Roland, where the Christian knight and his crusaders were caught and slaughtered by the Moors as they retreated into France in the 8th century.

Raincoats show their flaws, boots are sodden, packs become heavy, uphill is foreboding and constant, wind and rain are cyclonic. Reaching the hostel, persevering, becomes a quest; a shower, dry clothes, a hot meal and a warm bed await at the first Albergue, We’ve survived.

Along the Way – Finding the Rhythm

Walking consumes me, takes all my oxygen; I am obsessed, there is nothing else. It’s what I do, it’s the only thing I do.

Walking is,

weather is,

the Way is.

No trail finding skills necessary, no maps required, follow the signs.

Stay on the Way,

thirty days they say,

walk every day.

Routines emerge and harden; wake early, pack up gear, gulp a hot, bitter coffee, grab a pastry and set out; sunrise is best. When the sun is high, stop for second breakfast, another coffee and another pastry. Walk to day’s end, the chosen Albergue. Check in, unpack, shower, wash today’s clothes, put on tomorrow’s, rehydrate, nap, stretch. Commune with pilgrims; where are you from, why are you here, how are you feeling? Dinner is at 7, everyone is asleep early. Do the same for as many days as it takes to arrive at the Cathedral, to pay homage to the bones of Saint James that aren’t the bones of Saint James.

Fill the Void

Life on the Way is a void, no distractions; the outside world has ceased to exist. I walk alone.

The silence, the emptiness, the lack of distractions create a void unlike anything experienced; the void demands to be filled. It is. Wild fennel grows along our path; I rub its seeds in my hands, rewarded with the pungency of dill and anise, indelible, now forever the smell of the Way. Sunflowers offer a canvas to passing pilgrim artists to create happy faces to tickle my whimsy.

Early mornings are exhibitionists; the air is cool and fresh, the sky still filled with stars, sometimes a waning moon shines so brightly that my headlamp is superfluous. Mists swirl and curl, delineating contours of the land with their ever-shifting shrouds. The sun consumes them, they evaporate, light fills the gaps, a nuanced colour palate emerges offering impressionist paintings, the real reward for early-birds.

Yellow arrows become luminous neon signs. Each day’s first familiar arrow on a wall, a curb, a pole is my reassuring security blanket; I’m on the Way!.

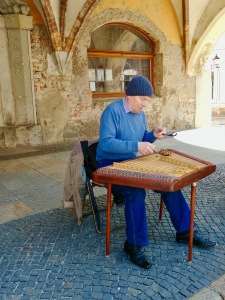

Crowing roosters, cowbells, church bells off in the distance add melodies to my morning reverie. We walk from church to church, rest stops full of aged piety, sanctuaries of quiet contemplation, a vesper service in the evening, a cool oasis from the energy-drained afternoon slog.

Fellow Pilgrims

We are pilgrims for a reason, each searching for something different; some not admitting, most not knowing, what we seek, what we need, what we want, what to hope for. Something other than the bones of Saint James calls to us.

People insinuate themselves into my solitude. A troupe from PEI skips along like a traveling minstrel show, team t-shirts, a different color every day.

Three women, Birthe from Denmark, Jennifer from California and Sally from Victoria, bond like sisters in a day. Sally celebrates her 65th, I’m invited to join.

Jeanette, a petite grandmotherly woman in her 70’s, looks more at home in her kitchen. She lost her husband; rather than sink into mourning, she decides the Way is the way out. Her electric bike, her Rocinante, takes her to Santiago. Over a pilgrim dinner; she tells of sadness slowly being replaced by hope and joy. We meet again in Santiago; we hug, I shed a tear, lifted up by all that she is and all that she will be. Buon Camino.

Arrival – October 15, 2013

Arrival is sweet/bitter. The sweet is joyful, euphoric – deeply satisfying. Gratification, much delayed, is at hand. Attendance at the daily pilgrim mass in the Cathedral bookends the Way: closure, my exclamation point. Priests swing a monstrous cauldron of burning incense down the length of the cathedral and back; rumour has it the incense tradition was started to cover the malodor of pilgrims.

The comes the bitter. It’s over; the void opens, I look into the abyss.

Peggy Lee emerges, stage left, singing “Is That All There Is?”.

No grand epiphanies, no insights into my soul, no nostrums on to how to lead ‘the good life’. The true gifts are the kindness of strangers, quiet, finding comfort in aloneness, a reconnection to the simplicity of nature, reawakened awareness of tiny pleasures, the physicality of walking, gratitude for gifts unexpected.

Second Stage – the Camino Portugues – 600 Kilometres

Lisbon, March 1, 2015

The Camino Portugues is a 600 kilometre pilgrimage from Lisbon to Santiago; it is sparsely traveled, fewer than 1000 pilgrims a year, lacks convenient amenities like hotels, hostels, restaurants, compensated by good signage, hospitable people and bread, extraordinary bread.

Slow down, again.

Spring in Portugal is idyllic, sunny and cool, farmers are in the fields, trees are blossoming, flowers are blooming, birds are singing. The pungency of fresh pig manure offset by the earthiness of freshly plowed soil ignite memories of a small-town in Alberta, long ago and far, far away. The scent of the baker’s fresh bread at the edge of the village; I sniff it out like a hunting dog. Again attuned to the delicate sensual possibilities of my surroundings. Dawn brings the morning dew, that dew captured on a spider web in morning’s soft golden light reveals its intricate architecture. My crowing roosters, my cow bells mingling with my church bells.

There is no clock but the sun, I lunch when the locals stop; their food, at their pace, leisurely, with appreciation. A park bench for siesta as the shadows grow in the afternoon.

Alone not Lonely.

Walking offers solitude; the emptiness opens room for awareness of the delicate, the whimsical, the ethereal. Without distractions, with abundant time to meander, my mind wanders further afield, seeks out distant recesses, rediscovers oft-forgotten memories. The interior space offers its own amusements, contemplations, dreams. The Knights Templar, a Catholic order of the 12th and 13th centuries, the Church’s warrior monks had their own castle in Tomar. Envious Kings and Popes disbanded the order, took their money, hunted them as fugitives. I create stories of those Knights Templar; heroes of my dreams, I join them for an adventure.

In the Company of Strangers

Evenings are amenable to the company of strangers, evening meals break the fast of aloneness. We walkers, it seems, are more honest, more revealing, more vulnerable, more open to dialogue. We gather for the pilgrim meal; a young man arrives in a flurry, late. A cyclist with wild Rastafarian hair, a bit ragged around the edges, a vast array of tattoos; my privileged white man bias tags him as an English Football hooligan. I name him Hooligan Harry.

“Oh great,” I think, “another night at the Bates Hotel”.

Our ragtag pilgrim group morphs into a fraternity of fellow travellers. Past travels, recent adventures, the philosophy of life, religion, football, human discourse at its best. Hooligan Harry is transformed into Renaissance Harold, a modest, thoughtful carpenter on a two year drop-out bike trek. Note to self, be aware of the fallibility of quick judgements.

Ruts as old as time.

The pilgrim path follows the Via Roma XIX, created by the Romans in the first Century AD; a path so eroded by the passage of feet and time, now several feet below the surface of the forest. Bridges built centuries ago, repaired, provide pilgrim’s crossing connecting an age-old road: my trek again shared with the Centurions.

Tender Mercies

In silence, uncluttered by noise and sensory overload, I become aware of nuances, subtleties and pleasures of human interaction, the kindness of strangers. I call them Tender Mercies. Drowned out in normal life, Tender Mercies are the oft-passed over, gossamer soft, fleeting, under-observed kindnesses of strangers brought to life. I catch them in the net of my empty mind. I play with them, shine them up, build stories around them, place them on my mind’s mantel, save them for special moments of remembrance. Later, as I roll them over in my brain, they bring smiles, driving away the lows, the sadness and the darkness.

In Golega, the O Te restaurant/hotel, I’m refreshed by a second floor room, a suckling pig dinner, a morning espresso and insightful philosophical musings from an elderly French Moroccan who somehow ended up as a hotelier in rural Portugal.

Miguel and Jennifer introduce me to Porto, their beloved city, an excursion ending with a match at FC Porto – futball, the other religion of Portugal.

At Meson Pulpo, near San Amaro, I stop for my late morning coffee. Filled with warmth, I decided to rest, absorb the serenity, eat. I order a bacon bocadillo – such lovely words, bacon bocadillo – I taste the words, even before it arrives. I savor my bacon bocadillo, the aroma of the soft chewy bun, the crunchy, hot, greasy, salty, bacon.

This restaurant is their home. I was their guest, radiant in their kindness, warmth, generosity, calm. Reluctant to go, reluctant to see me leave. That moment, my only human contact of the day; these are Tender Mercies.

There are sweet spots, fireflies of bliss, frozen in a minute. Ponte de Vila; a town of sublime beauty, shows deep respect for its history mixed with surprising modernity. Portuguese bread. Fresh fish, every piece cooked to perfection. Portuguese tiles turn buildings into art. The Portuguese tortilla, elevating potatoes to their rightful place as national cuisine. Bacon Bocadillo! Sweet spots, brief magical moments over which pixie dust is sprinkled. They don’t arrive easily; they last forever, their fleeting evanescence filling my mind’s void.

Third Stage – 88 Temples – 1400 Kilometres

Takushima, Shikoku, Japan April 1, 2016

The 88 Temples pilgrimage honors Kobo Daishi, a 10th century Japanese monk, instrumental in bringing Buddhism to Japan. 150,000 pilgrims annually replicate his travels. Daunting. A walk through time. A meditative search for Buddha. A stroll through rural Japan. Daunting, indeed.

Becoming a Japanese Pilgrim.

A Henro, a pilgrim, dresses to celebrate the ritual of pilgrimage. Requirements:

– a light white cotton vest/jacket representing purity and innocence.

– a sugegasa, a sedge hat, a portable, hands-free umbrella, protection from rain and sun, surprisingly comfortable.

- the kangozue, a long wooden walking stick topped with woven silk and a bell. Kobo Daishi’s spirit walks with us in our staff. It must be cared for, cleaned after every walk,

- – a Zudabukuro, a shoulder bag to carry candles, name slips, coins, incense sticks, and my precious stamp book, to honour temple rituals.

– an ample supply of curiosity, humility and gratitude.

I have no north star, no compass, no past experience, as close to explorer as today’s connected world allows.

Temple Serenity.

Each temple is unique, yet certain rituals are universal. Usually, after climbing stairway after stairway, the Henro reaches the gate. Henro pauses and bows, enters the temple grounds. To purify, Henro washes hands at a ceremonial basin, sips/spits a bit of well water to cleanse the mouth to enter the temple free of the dust of the journey. At the bell tower, Henro rings a massive brass gong – just once, more is bad luck. In the main hall, a name slip on which is written a short prayer for loved ones, is placed in a box. Three sticks of incense and a candle are lit and a donation placed in the offering box.

Henro becomes me. I say my prayers. I pause. There is a colour, a purple, that is so regal I automatically bow to it, subjecting myself to its majesty. If I am fortunate, other pilgrims are chanting sutras, magical, lilting songlike. I listen, eyes-closed, transfixed, transformed and transported to another time, another place, another world. Still in the sutra’s aura, I sit quietly, solemnity seeping into my bones, a singular peacefulness, a warm blanket of serenity.

I rouse myself, meander over to the Buddhist monk on duty, receive my temple stamp certified by a magnificent elaborate calligraphic flourish. We smile, acknowledge each other, a gift as valuable as the stamp. Exiting the temple, I bow to say goodbye.

The privilege of Pilgrims.

On a cloudy morning with rain a definite likelihood, I walk through a small village, approaching a tiny elderly woman pushing her rolling portable chair. Stooped over, her back carries a lifetime of toil, of hand-planting a million rice shoots one-by-one. She looks at me, I pause and bow. She glances at the sky, I look up too. She looks back at me. I look back, respectfully. She holds up her umbrella and gestures for me to take it. Smiling, I shake my head no. We engage in a non-verbal test of wills. Will I take her umbrella? How can I take her umbrella? How can I say no graciously? She insists! I can’t take her umbrella. Finally, to break the impasse, I walk over to her, bow many, many times and give her a Canada pin. I refuse the umbrella, politely but firmly. We reconcile, we bow. I wander off, marveling at her aggressive generosity.

It doesn’t rain.

A bus driver adopts me, foreign Henro, abandons his passengers, jumps out of his bus and shows me where I need to go, patiently waiting till he’s assured I’m on the right path. His passengers don’t seem to mind.

A man sees me walking past his home, rushes out, chases me down the street, catches me, bows, presents a small glazed clay pilgrim statue to carry on my pilgrimage.

The Japanese might have invented Tender Mercies.

For the love of blossoms

Blossoms burst into view, deep lipstick pinks, soft pastel white-pinks, every hue in between; across the field, a single cherry tree blazes pink amidst a forest painted the special greens of newly unfolding leaves, too many shades of pink and green to calibrate, each an affirmation of vitality and promise. Irises everywhere, splashes, slashes of brilliant purple accentuate the greens and pinks. At temples, umbrellas protect flowers from the rain so they may blossom fully. In the forests, bamboo, gently wave in the wind, next to pine trees that barely waver.

Japanese Koi nobori – elongated, hollow, multi-coloured kites on high poles wave in the breeze – part streamers, part kite, part flag, funny carp-looking streamers swimming in the blue wind – spring’s hopes in a kite.

Japanese farmers, artisans of the earth, meticulously manicure their plots: they work the soil, rice planted here, winter wheat ripening there, bags of onions harvested alongside Japanese radishes, a few frogs, two snakes.

Small plots where mechanical planters immerse tender shoots in water without maiming them; infinitely superior to one-at-a-time hand planting. Derelict houses witness the exodus of young people to the city, neglect amidst the farmers’ verdant crops.

Mountain paths, misty and mystically enhanced by aged Buddhist and Shinto monuments, stand silent, commemorating centuries of walkers. Paths are littered with monuments and statues, many adorned with brightly coloured knit caps, bibs and capes; offered up to the gods to keep them warm and save them from chills. Graveyards with ancient headstones – Shinto shrines – placed long before and long after Kobo Daishi and his Buddhism encroached, speak for another, more animist, religion, silently resisting the Buddhist invader.

Home not home.

Traditional Japanese hotels, ryokans, offer a simple room covered with Tatami mats, futons on the floor for sleeping and a toilet/sink. It is easy to go to bed, just flop down and pull the covers over you. Getting up is tougher. Done in stages, stiff muscles roll over onto all-fours, kneeling, lifting, finally upright, noisy and ungainly. Thankfully there are no witnesses.

Toilets designed by a techno-madman; a terrifying array of buttons offering options to do things to my bottom that are unimaginable. I touch none, barely trusting the normal flush lever.

Several pairs of slippers are provided, guests remove street shoes at the door and put on floor slippers, then remove floor slippers to put on room slippers; there’s usually a special pair of bathroom only slippers. No exceptions. Do not mix them up.

Onsen, Japanese communal baths, require special tourist courage. Segregated but public, very public. I wash, thoroughly, publicly, noisily, nakedly with the rest of the male bathers, then I bathe with them – again naked. Like the water, it is all too hot. I retreat to my room, red-faced but cleansed. This home doesn’t feel homey.

Food for the Epicurious

Meals are for the epicurious. Rice, salad, soup, fish bits, pickled vegetables – breakfast at the traditional Japanese hotels. Foraging for lunch is more familiar. Convenience stores, astonishingly, offer fresh full nutritious meals for the pilgrim walker. Lawson is my favourite, offering food, an ATM and wifi – sustenance, cash and contact with home, convenience redefined. Restaurants offer pictures and odd little plastic replicas of the dinner menu items. Sushi is my mainstay; the sushi-chef in his special jacket, shirt and tie is king. I give him respectful license to feed me, he’s never wrong.

Visual presentation and display are carefully considered. I am advised to pause a few minutes to observe and take pleasure in the beauty of my food – art enhances the dining experience.

Koyo-san

The Buddhist monk stamps my book, my 88th stamp, signs it with his elaborate calligraphy. I’m done. I give my staff to the caretaker, they are ceremoniously burned as a sacrifice. A new pilgrim in my hotel takes my sedge hat, the rest of my uniform and my stamp book are mine. I board the bus to Koya-san, a temple rich village in the mountains above Kyoto to pay respect to Kobo Daishi. He is here, in eternal meditation. Eternal meditation sounds so much more dignified than death.

Down and done

It’s not all fun and games. I’m drained. I spend my last few days in Kyoto, drinking coffee at Starbucks, reading the International New York Times, eating egg salad sandwiches, listening to a Japanese curated playlist of best American hits of the 50’s and 60’s, trying to cover myself in a warm blanket of the familiar till Air Canada takes me home.

Fourth Stage – The Via Francigena – 2000 Kilometres

1 – Canterbury, England – Reims France July 16, 2017

2 – Reims, France – Ivrea, Italy July 16, 2018

3- Ivrea, Italy – Lucca, Italy, September 2, 2021

4- Lucca, Italy – Rome, Italy, April 16, 2022

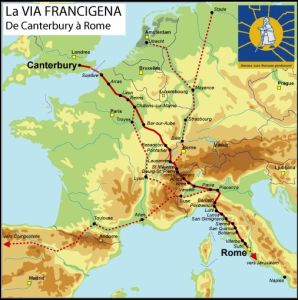

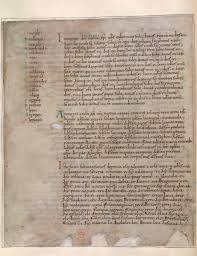

In 990 AD, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Sigeric, walked to Rome to be confirmed by the Pope as a Cardinal, his return trip chronicled, 79 stops preserved on a single sheet now preserved in the British Museum. His journey inspired the Via Francigena. With only 2500 pilgrims annually, it’s a lonely walk. Yet, through the years, through invasions, wars, the plague, predation from two and four-legged animals, scorching summer sun, freezing Alpine passes, pilgrims have endured, walking to Rome to seek enlightenment, forgiveness of past sins, healing.

Motivations as varied as the human condition.

The comfort of the familiar

After Japan, walking the VF is like putting on a pair of old slippers. My pack is light, I have my guidebook, my passport and my credit card. My old routine still works, a study in positive addiction. I rise, eat, drink and walk – stay on path, observe the scenery and its minute miracles. Hours of mindful vacancy are my familiar rewards. It feels good. Another day done, I dump my pack, wash my clothes, eat simple French rural food at its best. I sleep well.

I am where I want to be, walking my path, reacquainting myself with tiny miracles of a flower, a sunrise, mist, cool water, a simple buttered baguette, a wave to the locals as I pass through near abandoned villages,

Walking through History.

Kristen is with me for a while. In northern France, remnants of the great war share their horrors. A small cemetery, populated with random crosses – French, Belgian, English, German, an occasional Canadian define the losses at a field hospital. Hospitals at the front took anyone brought to them; death took its share, they were buried together without discrimination. Here no one was friend or enemy, no one won – war’s cruel egalitarianism.

Bapaume has a Sunday circus. Serendipitous surprise, we arrive in time for the parade! We drop our packs, find French profiteroles, carny pastry at its best and pull up a piece of curb to watch – unexpected, enthralling entertainment. We saw camels!

Villages, hollowed out by farm consolidation, efficiency and the inevitable migration to cities, leave only the elderly and the stubborn; a rich tapestry of rural French life gone – old people, old ways, churches decimated of congregations, priests and abandoned beliefs. The ultimate indignity, a bread dispensing machine – even the fresh baguette has been forsaken.

Much is left to appreciate; rolling hills, the wheat fields golden, heavy and ready for harvest, a donkey shocking us with his ungodly bray, the sheer joy of walking, the blessing of companionship, the connection with weather, land and the ground beneath our feet. The simple joy of a ham and cheese baguette, a drenching summer rain showering our sense of humour, the celebratory glass of champagne for my daughter/companion, the pride of accomplishment in achieving something that can only be gained by one measure – footsteps.

Reims, the city of kings when kings mattered, is now more famous as the home of Champagne; more venerated than generations of kings buried at the Cathedral.

Walking alone or together.

I travel alone, pilgrim journeys are solitary by choice. Alone does not mean lonely, one does not have to be an introvert to realize that some activities are best experienced on one’s own. It’s called being comfortable in one’s own skin.

A proper companion adds to solo walks. My daughter Kristen and I walk well together; long silences, mutual chatter, a few deeper conversations, some code-talk decipherable only to us, years and years of old dead-cat bounce jokes.

On the next leg my friend John walks with me from Reims to Besancon. The perfect walking companion, quiet till he has something to say, amiable to a fault, pleasant dinner companion and roomie, adding bright and shiny observations, new dimensions, to the journey.

A summer heat wave defines this walk. Hollowed out rural France limits our options, access to water becomes an overarching necessity, finding sanctuary in shade – straw hats, a tree, the cool church – weather rules at 30+ degrees. We hitch rides, hire taxis, start earlier, anything to reduce our walking time under the relentless sun and heat. The pavement softens.

Up and Over

The Great Saint Bernard Pass is the halfway point of the VF. A Roman gateway to Europe before the birth of Christ; Napoleon marched back to attack the Italian city states in 1800. At 2473 metres, it is formidable; travel by foot is only possible in July and August.

Blair joins me in Lausanne, five days up to the top of the pass. It’s not easy. I struggle, grateful for his presence, his support and his encouragement. It’s always a test of will over wish.

Late afternoon, within sight of the summit, Blair surprises me. We find a flat rock, drop our packs, sit; he pulls two Astronaut-ready freeze-dried ice cream sandwiches from his pack, feeding my legendary love of ice cream. We sit on our rock, basking in the sun, and savour our treat. Priceless.

Icing on the ice cream, a young woman appears, out for a walk with three Great Saint Bernard dogs, sent by the gods to guide us through the Great Saint Bernard Pass.

Pandemic interlude

If you want to hear the gods laugh, tell them your plans for the future. Life’s distractions necessitate a year’s delay; then covid closes all doors. We hunker down; a trip to buy groceries becomes unthinkable, Italy, impossible. Doubt creeps in, fear its companion. Anxiety and the desire for safety inflates risks, problems, what-ifs. Lethargy kills dreams. Months of whiling away hours, the only goal being to while away the hours. Has the joy of adventures lost its joy?

A window opens in autumn of 2021. Italy’s vaccination rates are high, infections are down, hospitalizations down, deaths down. Travel restrictions are loosened, BC immunization cards are recognized by Italian authorities. Walking in rural areas with minimal contact with others; no more hostels, my own hotel room, tough Italian no-nonsense rules. Needless risk is not smart, minimizing risk is. It’s worth the risk.

I have unfinished business, it’s time to go.

Italy – fountain of renewed faith

Ivrea to Lucca; down out of the Alps, across the Po valley, over the Apennines, into Tuscany – 450 kilometres in all. The Po Valley is famous for growing risotto, a signature dish for Italian cuisine. Rice growing requires flooding; water being what it is, flood irrigation requires flat land – relentlessly flat land. A complex grid system of canals, ditches and sliding gates has been created to ensure the channeling of river water across vast distances to irrigate the valley, a massive engineering project worthy of the plumbers who brought us aqueducts 2000 years ago. Flat is good for walkers.

Familiar ways of seeing

The Po Valley offers rural ambling at its best, especially early mornings. The misty coolness, the scent in the air, surprised little beasties – rabbits, feral cats, cranes and herons, a dead snake. The dew on slender stalks of grass, the amazing light as it plays across the sky and the land; dark turns to dawn, dawn turns to morning. It is the magical part of the walking day. It’s also practical; the earlier the start, the sooner the finish – and out of 30+ heat. The now familiar rhythm of pilgrim walking is satisfying. Elemental, simple, rustic, like meeting an old friend.

Covid anxiety drains away like excess water into the channel.

My Passport

In Tromello, I stop for my morning coffee. While I’m resting in the small central square of this village, a spare, elderly man rolled up on an equally aged bicycle.

“Pelegrino?” He asked.

I nodded.

“Passport?”

I nodded again.

He motioned that I should give it to him.

I did.

He rode off.

Pelegrinos carry a pilgrim passport. We collect stamps from hotels and churches to verify our passage. It’s like getting stars in your school workbook. It’s oddly satisfying.

In a few minutes he returned, his church stamp proudly displayed in my passport forever.

“Buon Camino.”

Grazie mille.

We finished the formalities, smiled to each other,

Off he rode.

Such Tender Mercies…

Crossing the Po

Danillo has been running a ferry for pilgrims to cross the Po for 23 years. He is a legend; ferry boat captain, historian of the VF, certifier of passage and keeper of the Big Book. The night before our crossing, I stay at the hostel in Corte S. Andrea right beside the Po River. There is an Osteria close by; it’s Sunday, long Sunday family lunches are a tradition. I arrive unannounced, bedraggled; a table is set up, I’m fed like a prince. They give me the hostel key, I wander over, find a bed. Giovanni and his wife, voluntary caretakers both in their 80’s, pop over to welcome us. Kindness isn’t always large and dramatic, sometimes it’s daily and small.

Next morning we meet Danillo. Well into his elder years, he captains his boat across the Po, ferries pilgrims, offers a history lesson and permits us to sign his pilgrim ledger, the Big Book.

It leaves passengers giddy.

Over the Apps.

The Appenines are the last serious elevation on my way to Rome. Wild animals set paths long ago that followed contours, not losing elevation unless necessary. Smart people followed the animals, turning their trails into paths. VF planners ignore contours, plot a bizarre path with needless ups and downs. I follow contours, plot shortcuts, muttering vile threats. I hope I’m right.

First day is 20 km with about 1000m of elevation. After an early morning train ride, I reach my B&B, check in with Manuella, drop the Beast and manage to make it to Cassio. I am grateful that, after much huffing and puffing, vehement curses on the heads of route planners and a brief storm, I arrive in time for my afternoon espressos. The local bus arrives, I make it home In time for a shower and dinner. Slick! Damn I’m good!

Day two is shorter, 10 km and 300 m of elevation. Saturday, only a few buses run. I hitched a ride to Cassio, did my walk to Bercetto and caught the ONLY bus back home – again in time for dinner.

Hah! Easy peasy!

Third day, there are no buses on Sunday! Major tactical flaw, no plan B.

Crap. What now!

Manuela, my saviour, manufactures a new plan and we move; she calmly feeds me breakfast, drives me to Bercetto, drops me off at my B&B, perfectly positioned for my final day. In doing do, she sacrifices hours of time, a busy B&B and kilometres of driving to move me forward. The final day, I quick-march to the summit, stroll 22 kilometres downhill to Pontremoli.

Victory achieved. That wasn’t so bad, I think. Why was I so worried?

It was Manuella who made it not so bad. She rescued me, the saint of Tender Mercies, proof again that one doesn’t always walk alone, that ups and downs can be navigated by following the contours.

Wading through Italian history.

A walk to Lucca is a walking history lesson. The landscape, rolling hills and valleys, rugged forests broken occasionally by pastures and crops, strung together by small villages. Pontremoli, a fortress town controlling access to two valleys and lands above and below for centuries, houses a museum of stele discovered nearby dating back to the 3rd/ 4th century BC.

Filleto, a fortress of its own, is Saracen, another word for the Moors – invaders, bandits and raiders who dominated much of the Mediterranean for centuries.

After Filleto, I walk a road that dates back to the Roman Empire. With everything measured in seconds and sound bites, to walk the footpath Roman armies used to cross the Alps more than 2000 years ago, used for so long that the road is sunk several feet below the forest floor brings perspective to the quicksilver of immediacy.

Luna offers proof that Carrara marble has been used from Roman times. Carrara quarries are famous since the golden age of Rome; Michelangelo’s David, marble from Carrara, has the unsurpassed purity of the white Carrara marble.

Saint Michele Paolino Cathedral in Lucca, fittingly clad in Carrara marble, I receive my pilgrim stamp, the end of this section. The final walk, 350 kilometres fromLucca to Rome, is – like life – to be continued.

The Polish author, Ogla Tokarczuk, a Nobel Prize winner, develops her idea of synchronicity:

“…evidence of the world making sense. Evidence that throughout this beautiful chaos threads of meaning spread in every direction.”

The land is portioned off by stone fences. Loose stone gathered from fields piled without mortar in a linked, orderly manner to be virtually indestructible. They go on for miles. They amaze me. I think the word is gobsmacked. I’m equally impressed by hedgerows, ancient tangles of bushes, virtually impermeable, a living home for rabbits and other beasties. Rural England fields, delineated by hedgerows and fences, are easily traversed however by right of passage paths; in most of the UK, a person can walk across a farmers field with impunity, although death-by-surprised/angered-cow happens more often that one might expect. It’s a Canadian hiker’s dream.

The land is portioned off by stone fences. Loose stone gathered from fields piled without mortar in a linked, orderly manner to be virtually indestructible. They go on for miles. They amaze me. I think the word is gobsmacked. I’m equally impressed by hedgerows, ancient tangles of bushes, virtually impermeable, a living home for rabbits and other beasties. Rural England fields, delineated by hedgerows and fences, are easily traversed however by right of passage paths; in most of the UK, a person can walk across a farmers field with impunity, although death-by-surprised/angered-cow happens more often that one might expect. It’s a Canadian hiker’s dream. I’m also impressed by the quality of the mud here. March was the wettest on record in the Cotswolds. The Windrush river is high. Puddles abound especially around a plethora (love that word, had to use it; forgive me) of gates all ingeniously designed to befuddle sheep and foreigners. Foolishly, we try to stay clean and dry on our walks. A quarter hour in, I give up. Mud adds to the ambiance.

I’m also impressed by the quality of the mud here. March was the wettest on record in the Cotswolds. The Windrush river is high. Puddles abound especially around a plethora (love that word, had to use it; forgive me) of gates all ingeniously designed to befuddle sheep and foreigners. Foolishly, we try to stay clean and dry on our walks. A quarter hour in, I give up. Mud adds to the ambiance.  We stopped at a small village green for a standup lunch. There was a checkin for some local event close by so we wandered over to see what it was about. Think of a treasure hunt with multiple stops, the avid participants being vintage motorcycle owners. In England there is a club for almost every interest; all taken seriously, all pursued with joyous concentrated eccentricity. A perfect example appeared in a puff of smoke – a couple on a motorcycle and a sidecar rolled in.

We stopped at a small village green for a standup lunch. There was a checkin for some local event close by so we wandered over to see what it was about. Think of a treasure hunt with multiple stops, the avid participants being vintage motorcycle owners. In England there is a club for almost every interest; all taken seriously, all pursued with joyous concentrated eccentricity. A perfect example appeared in a puff of smoke – a couple on a motorcycle and a sidecar rolled in.  England is littered with history; celebrated, discussed and debated as if it still mattered. We casually visit small Norman churches that go back to the 12th century. Bourton-on-the-water is a perfect village, our home for the week, all golden cottages, picturesque pubs and stone bridges crossing the Windrush River, Upper Slaughter, a village close by even has a water wheel, still turning after all these years.

England is littered with history; celebrated, discussed and debated as if it still mattered. We casually visit small Norman churches that go back to the 12th century. Bourton-on-the-water is a perfect village, our home for the week, all golden cottages, picturesque pubs and stone bridges crossing the Windrush River, Upper Slaughter, a village close by even has a water wheel, still turning after all these years. Next week, I exchange the rolling hills, quaint golden cottages and bursting-with-spring-green meadows of Bourton-on-the-Water for the rugged, wind-sculpted upsy/downsy terrain of Cornwall; defined by the ocean, cliffs and abandoned tin mines. It’s as desolate looking as the Cotswolds were lush.

Next week, I exchange the rolling hills, quaint golden cottages and bursting-with-spring-green meadows of Bourton-on-the-Water for the rugged, wind-sculpted upsy/downsy terrain of Cornwall; defined by the ocean, cliffs and abandoned tin mines. It’s as desolate looking as the Cotswolds were lush.  A slight digression if I might be allowed. At St.Just, I was compelled to sample my first.original pasty (pronounced with a soft ‘a’ like pasta). One cannot pass a shop that claims to be the oldest maker of Cornish Pasties. It would simply be wrong.

A slight digression if I might be allowed. At St.Just, I was compelled to sample my first.original pasty (pronounced with a soft ‘a’ like pasta). One cannot pass a shop that claims to be the oldest maker of Cornish Pasties. It would simply be wrong. Our walks along the Coast Trail are amazing confirmation of my desire for the experience. I choose the shortest of the daily walks – about 8 km. We ramble about for 4-5 hours, view the scenery, learn some fun facts, most of which I immediately forget. I have my own room, meals, a packed lunch and a guide. I am getting an April tan. I become mildly addicted to canned pork and beans on toast for breakfast, as close to a vegetable as I can find. The English still seem mystified about how to cook vegetables; Ottolenghi is trying.

Our walks along the Coast Trail are amazing confirmation of my desire for the experience. I choose the shortest of the daily walks – about 8 km. We ramble about for 4-5 hours, view the scenery, learn some fun facts, most of which I immediately forget. I have my own room, meals, a packed lunch and a guide. I am getting an April tan. I become mildly addicted to canned pork and beans on toast for breakfast, as close to a vegetable as I can find. The English still seem mystified about how to cook vegetables; Ottolenghi is trying. Stories abound of resourceful Cornishmen who, not looking forward to a nasty, brutish and short life toiling in a tin mine, took matters into their own hands and became experts at salvaging whatever drifted ashore from wrecked ships. While lighthouses did exist to guide ships away from rocks and harm, enterprising Cornishmen were known to create illicit lighthouses, carefully designed to lure ships onto the rocks. The Cornish version of Robin Hood.

Stories abound of resourceful Cornishmen who, not looking forward to a nasty, brutish and short life toiling in a tin mine, took matters into their own hands and became experts at salvaging whatever drifted ashore from wrecked ships. While lighthouses did exist to guide ships away from rocks and harm, enterprising Cornishmen were known to create illicit lighthouses, carefully designed to lure ships onto the rocks. The Cornish version of Robin Hood.  I learned new definitions for a couple of common words that impressed upon me the English capacity for understatement.

I learned new definitions for a couple of common words that impressed upon me the English capacity for understatement.

I grew up in a small town in southern Alberta, Taber, known for agriculture – sugar beets and corn – not ideas. It was however a surprising melting pot of people from other places, farmers, second generation immigrants, my own Welsh coal mining grandfather, various forced relocatees – the chinese, japanese, czechs, hungarians; all bringing their baggage and their cultural uniqueness and, their religions to this small remarkably diverse town.

I grew up in a small town in southern Alberta, Taber, known for agriculture – sugar beets and corn – not ideas. It was however a surprising melting pot of people from other places, farmers, second generation immigrants, my own Welsh coal mining grandfather, various forced relocatees – the chinese, japanese, czechs, hungarians; all bringing their baggage and their cultural uniqueness and, their religions to this small remarkably diverse town.  Taber had a library. It was housed upstairs from the local firehall, close to downtown; although everything in Taber was close to downtown. I like to think looking back that its location was portentous, while the firetrucks below were there to put out fires, the library above was there to start them, to offer books to inflame the minds of readers. There’s a new one now, thankfully bigger, more accessible, more animated, more welcoming.

Taber had a library. It was housed upstairs from the local firehall, close to downtown; although everything in Taber was close to downtown. I like to think looking back that its location was portentous, while the firetrucks below were there to put out fires, the library above was there to start them, to offer books to inflame the minds of readers. There’s a new one now, thankfully bigger, more accessible, more animated, more welcoming. It worked for me. One of my favorite memories of Taber involves the library. After supper, I would pick up my friend, Rod Adachi; we’d cross the tracks to downtown and head for the library. We’d both wander through the stacks (about 3000 books by then) and choose our full allotment – I think four was the limit. We’d wander home and repeat the process every week. Each week, I had four remarkable adventures, the Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew series stand out. It was inflammatory; I may have left Taber long ago but I never lost my love of books as a gateway to adventure, vicarious adventure but adventure nevertheless.

It worked for me. One of my favorite memories of Taber involves the library. After supper, I would pick up my friend, Rod Adachi; we’d cross the tracks to downtown and head for the library. We’d both wander through the stacks (about 3000 books by then) and choose our full allotment – I think four was the limit. We’d wander home and repeat the process every week. Each week, I had four remarkable adventures, the Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew series stand out. It was inflammatory; I may have left Taber long ago but I never lost my love of books as a gateway to adventure, vicarious adventure but adventure nevertheless.  I found Beryl Markham at the Joe Fortes branch of the Vancouver Public Library, next to the West End Community Center – a ten minute walk from my home. You can often find me there, my gateway to adventure, along with adventure seekers of all ages, looking for another book by Beryl Markham.

I found Beryl Markham at the Joe Fortes branch of the Vancouver Public Library, next to the West End Community Center – a ten minute walk from my home. You can often find me there, my gateway to adventure, along with adventure seekers of all ages, looking for another book by Beryl Markham.

Let’s go back to Beryl Markham. West with the Night inflames the imagination. I had the great joy of taking my children, Blair and Kristen and Kristen’s husband Chris, to Africa. We spent some time in places where Markham grew up, a century earlier. Her stories reignite the tingly excitement, the awe, the jaw-drop of wonder that we experienced.

Let’s go back to Beryl Markham. West with the Night inflames the imagination. I had the great joy of taking my children, Blair and Kristen and Kristen’s husband Chris, to Africa. We spent some time in places where Markham grew up, a century earlier. Her stories reignite the tingly excitement, the awe, the jaw-drop of wonder that we experienced.  We had seen warthogs from the safety of our land rover. They are not domestic pigs, as geckos are not crocodiles; they are much to be feared. Markham describes the warthog brilliantly:

We had seen warthogs from the safety of our land rover. They are not domestic pigs, as geckos are not crocodiles; they are much to be feared. Markham describes the warthog brilliantly:

On December 27, 1831, the HMS Beagle set sail from Plymouth England on a two year voyage to survey the coast of South America. On board was a young Cambridge academic – Charles Darwin. He was just 22. Few adventures could be ranked as so profoundly altering our view of the world as that of Darwin’s on the Beagle.

On December 27, 1831, the HMS Beagle set sail from Plymouth England on a two year voyage to survey the coast of South America. On board was a young Cambridge academic – Charles Darwin. He was just 22. Few adventures could be ranked as so profoundly altering our view of the world as that of Darwin’s on the Beagle.  Antoine de Saint-Exupery, famous for

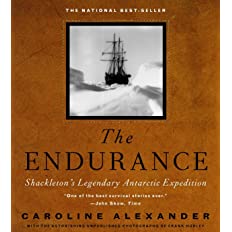

Antoine de Saint-Exupery, famous for  The Endurance by Caroline Alexander recounts the incredible experience of Ernest Shackleton and the crew of the Endurance on their expedition to Antarctica in 1914. Arriving in Antarctica, the ship became stuck in ice and eventually crushed; the crew abandoned the Endurance and engaged in an unparalleled struggle to survive and return to safety. The last of the 29 member crew were rescued in August 1916 – two years after the start of their ‘adventure’; a saved treasure trove of original unwieldy glass plate photos grimly testifies to their ordeal.

The Endurance by Caroline Alexander recounts the incredible experience of Ernest Shackleton and the crew of the Endurance on their expedition to Antarctica in 1914. Arriving in Antarctica, the ship became stuck in ice and eventually crushed; the crew abandoned the Endurance and engaged in an unparalleled struggle to survive and return to safety. The last of the 29 member crew were rescued in August 1916 – two years after the start of their ‘adventure’; a saved treasure trove of original unwieldy glass plate photos grimly testifies to their ordeal.  Adventures such as these are not reserved for men alone. Isak Dinesen,

Adventures such as these are not reserved for men alone. Isak Dinesen,  Two memories popped into my head as I stared out my window. I went on a Scottish Highland walk with Kristen a few years back. not surprisingly, we had a particularly Scottish highland day; rain, drizzle, mist and mud had soured my demeanour and curdled my enjoyment. I was not happy.

Two memories popped into my head as I stared out my window. I went on a Scottish Highland walk with Kristen a few years back. not surprisingly, we had a particularly Scottish highland day; rain, drizzle, mist and mud had soured my demeanour and curdled my enjoyment. I was not happy. On my latest pilgrimage, Blair and I were climbing the Great Saint Bernard Pass, a hard slog over the Alps and into Italy that I was not enjoying. A vague hope hovered in the air, Blair had promised a surprise when we reached the summit. Nearing the pass, I collapsed, a rest before the final 100 metres of push. We sat on a rock, the sun broke and Blair pulled two freeze-dried, astronaut-certified ice cream bars out of the bottom of his bag to celebrate our success. he’d thought of this weeks ago, bought them knowing they might be needed and offered them up to celebrate our achievement. My bad attitude disappeared, my joy emerged like the sun, I came to life.

On my latest pilgrimage, Blair and I were climbing the Great Saint Bernard Pass, a hard slog over the Alps and into Italy that I was not enjoying. A vague hope hovered in the air, Blair had promised a surprise when we reached the summit. Nearing the pass, I collapsed, a rest before the final 100 metres of push. We sat on a rock, the sun broke and Blair pulled two freeze-dried, astronaut-certified ice cream bars out of the bottom of his bag to celebrate our success. he’d thought of this weeks ago, bought them knowing they might be needed and offered them up to celebrate our achievement. My bad attitude disappeared, my joy emerged like the sun, I came to life. It occurred to me that I have been looking through the wrong end of life’s telescope. Life wasn’t shrinking, it was, if I let it, expanding. Walking slower meant more time for observation and reflection. Walking in the company of others allowed sharing, an intimacy that seems more valuable these days. Jumping in puddles can be a metaphorical talisman, if I allow it to fly free from the sad wet blanket I’ve thrown over it.

It occurred to me that I have been looking through the wrong end of life’s telescope. Life wasn’t shrinking, it was, if I let it, expanding. Walking slower meant more time for observation and reflection. Walking in the company of others allowed sharing, an intimacy that seems more valuable these days. Jumping in puddles can be a metaphorical talisman, if I allow it to fly free from the sad wet blanket I’ve thrown over it. I have been home for a while and reflecting on my recent trip, the end of a ten year/5000 km series of four pilgrimages. I’m asked, and I ask myself, what did I get out of it? It’s not like I have, for a decade, carried an expectation of some grand epiphany or some other-worldly instant conversion like Saul/Paul on the road to Damascus. Yet something should have happened after all those miles, all those days alone, all that time away from the worldly distractions; something worth mentioning. Something kept me at it. The good news is that there has been transformation – not fireworks in the sky – but slow, gradual, meaningful and hopefully permanent transformation of the way I live my life.

I have been home for a while and reflecting on my recent trip, the end of a ten year/5000 km series of four pilgrimages. I’m asked, and I ask myself, what did I get out of it? It’s not like I have, for a decade, carried an expectation of some grand epiphany or some other-worldly instant conversion like Saul/Paul on the road to Damascus. Yet something should have happened after all those miles, all those days alone, all that time away from the worldly distractions; something worth mentioning. Something kept me at it. The good news is that there has been transformation – not fireworks in the sky – but slow, gradual, meaningful and hopefully permanent transformation of the way I live my life. As for Catholicism, my personal experiences with organized Christian traditions and my jaded view of the impact of Christianity on people throughout history has made rethinking my beliefs a truly uphill battle, Sysiphus would have had an easier task.

As for Catholicism, my personal experiences with organized Christian traditions and my jaded view of the impact of Christianity on people throughout history has made rethinking my beliefs a truly uphill battle, Sysiphus would have had an easier task. There is a long tradition of serious philosophers rhapsodizing about the impact walking has had on their thoughts about the central question of philosophic inquiry. How do we live the good life? Walking seems conducive to thinking big thoughts. Philosophers since the Ancient Greeks have given considerable time and thought on how to live the good life by thinking while walking; the process seems to have failed me, I don’t feel much wiser about how to live the good life. As one Saturday Night Live actor said, “Deep down, I’m quite shallow.” – maybe that fits, or I can’t think deeply and walk at the same time.

There is a long tradition of serious philosophers rhapsodizing about the impact walking has had on their thoughts about the central question of philosophic inquiry. How do we live the good life? Walking seems conducive to thinking big thoughts. Philosophers since the Ancient Greeks have given considerable time and thought on how to live the good life by thinking while walking; the process seems to have failed me, I don’t feel much wiser about how to live the good life. As one Saturday Night Live actor said, “Deep down, I’m quite shallow.” – maybe that fits, or I can’t think deeply and walk at the same time.

But there is also agency. I can do something about it. I have a backpack cover to protect my possessions, they’re all I have. I have a cheap, lightweight raincoat that I can put on if it rains. My trusty walking fedora will keep the rain off my face and my glasses. I can do things to manage. That is agency.

But there is also agency. I can do something about it. I have a backpack cover to protect my possessions, they’re all I have. I have a cheap, lightweight raincoat that I can put on if it rains. My trusty walking fedora will keep the rain off my face and my glasses. I can do things to manage. That is agency.

Here’s a detail that illustrates. It’s the Easter long weekend. In Italy, it’s the big one. Everyone is on the move; places are closed. My much fantasized feast of fabulous Italian meals is delayed, it’s pizza joints staffed by kids who drew the short straw and had to work the Easter shift. Easter Monday was so bad that dinner consisted of a bag of chips and a coke zero from a sports bar. But, a bad Italian pizza gets more stars than most I’ve had in Vancouver.

Here’s a detail that illustrates. It’s the Easter long weekend. In Italy, it’s the big one. Everyone is on the move; places are closed. My much fantasized feast of fabulous Italian meals is delayed, it’s pizza joints staffed by kids who drew the short straw and had to work the Easter shift. Easter Monday was so bad that dinner consisted of a bag of chips and a coke zero from a sports bar. But, a bad Italian pizza gets more stars than most I’ve had in Vancouver.

I’ve managed to hit spring flowering season. My favorites – Irises – show off in more delightful variations of purple, white, yellow and blue than I have witnessed, perfect contrast to the green-spring palette. Grape vines are starting to sprout buds, the eternal promise of a bountiful harvest of grapes in the autumn. Olive trees abound, gnarly survivors showing their tenacity and age by their mis-shapened trunks. Winter wheat is more abundant than I expected.

I’ve managed to hit spring flowering season. My favorites – Irises – show off in more delightful variations of purple, white, yellow and blue than I have witnessed, perfect contrast to the green-spring palette. Grape vines are starting to sprout buds, the eternal promise of a bountiful harvest of grapes in the autumn. Olive trees abound, gnarly survivors showing their tenacity and age by their mis-shapened trunks. Winter wheat is more abundant than I expected.  As I follow the VF path, my stops usually take me to places of significance. Many such as Lucca, San Gimignano, Monteriggioni, Siena, and San Quirico d’Orcia owe their existence to the VF as important stops along the route. The VF became a source of commercial and artistic cross fertilization – pilgrims and others carried more than their packs with them and shared more than their food over dinner meals.

As I follow the VF path, my stops usually take me to places of significance. Many such as Lucca, San Gimignano, Monteriggioni, Siena, and San Quirico d’Orcia owe their existence to the VF as important stops along the route. The VF became a source of commercial and artistic cross fertilization – pilgrims and others carried more than their packs with them and shared more than their food over dinner meals.  Unfortunately, the rest of the day is cold and rainy, I’m holed up in cold drafty hotel rooms, with no heat; I’m given an extra blanket for comfort if not survival. Yet even that brings an adventure. I arrive just before rain in Viterbo, call the hotel and Paulo (I never knew his real name) comes and gets me settled. I always ask for a restaurant recommendation, serendipitously, he owns a place a few blocks away. I clean up and wander over. Paulo is the chef, the Chef!!!; he greets me like an old friend. I leave everything up to him and have the best lunch and dinner of the journey. For an afternoon, I felt at home, amongst friends – precious comfort for a man on the road.

Unfortunately, the rest of the day is cold and rainy, I’m holed up in cold drafty hotel rooms, with no heat; I’m given an extra blanket for comfort if not survival. Yet even that brings an adventure. I arrive just before rain in Viterbo, call the hotel and Paulo (I never knew his real name) comes and gets me settled. I always ask for a restaurant recommendation, serendipitously, he owns a place a few blocks away. I clean up and wander over. Paulo is the chef, the Chef!!!; he greets me like an old friend. I leave everything up to him and have the best lunch and dinner of the journey. For an afternoon, I felt at home, amongst friends – precious comfort for a man on the road.

In 990, Sigeric, Abbot of St. Augustine’s Canterbury and the highest ranking member of the Anglo Saxon Catholic hierarchy in Britain, received word that Pope John XV wanted to elevate him to the role of Cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church.

In 990, Sigeric, Abbot of St. Augustine’s Canterbury and the highest ranking member of the Anglo Saxon Catholic hierarchy in Britain, received word that Pope John XV wanted to elevate him to the role of Cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church.

What makes his pilgrimage notable is that one of his secretaries kept a careful log of his visits to 23 Roman churches over three days and recorded a daily log of his trip from Rome to Canterbury, a ‘guidebook’ in Latin of the stages and stops along the way.

What makes his pilgrimage notable is that one of his secretaries kept a careful log of his visits to 23 Roman churches over three days and recorded a daily log of his trip from Rome to Canterbury, a ‘guidebook’ in Latin of the stages and stops along the way.  There is nothing like walking a route traveled long ago to get some sense of what Sigeric experienced. While it was fraught with challenges, the route had been traveled for five or six centuries, Roman roads existed and continued to prove the remarkable and enduring talent of Roman engineering (we actually walked for part of a day on an old Roman road – straight as an arrow and still solid and passed an ancient Roman waystation that was part of a major Swiss archeological site).

There is nothing like walking a route traveled long ago to get some sense of what Sigeric experienced. While it was fraught with challenges, the route had been traveled for five or six centuries, Roman roads existed and continued to prove the remarkable and enduring talent of Roman engineering (we actually walked for part of a day on an old Roman road – straight as an arrow and still solid and passed an ancient Roman waystation that was part of a major Swiss archeological site).  In addition, monasteries, local and church sponsored charitable ‘hospitals’ purpose-built to serve pilgrims on their journey had been established that provided some rudimentary level of food and lodging along the way. (we managed to stay at a much refurbished hostel – now a Michelin starred destination restaurant/hotel – that sets its origins back to the 13th century)

In addition, monasteries, local and church sponsored charitable ‘hospitals’ purpose-built to serve pilgrims on their journey had been established that provided some rudimentary level of food and lodging along the way. (we managed to stay at a much refurbished hostel – now a Michelin starred destination restaurant/hotel – that sets its origins back to the 13th century)  The ancient Roman ruins were that – ruins. Major sites had fallen into disrepair, their stones cannibalized for church building, aqueducts had failed from lack of maintenance, the baths were dry and used more for itinerant housing, already less luxurious than in Rome’s halcyon days; even the Colosseum had become a large housing complex, filled with squatters. One of the few remaining sources of revenue seemed to be the thriving commerce of pilgrimage.

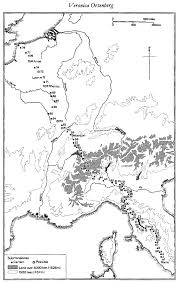

The ancient Roman ruins were that – ruins. Major sites had fallen into disrepair, their stones cannibalized for church building, aqueducts had failed from lack of maintenance, the baths were dry and used more for itinerant housing, already less luxurious than in Rome’s halcyon days; even the Colosseum had become a large housing complex, filled with squatters. One of the few remaining sources of revenue seemed to be the thriving commerce of pilgrimage. In an amazing feat of investigative academic research, there is almost universal consensus on the 23 churches noted in the diary of Sigeric’s visit to Rome, not a small task given the age of the document, the many possible interpretations that might have been given to some obvious mis-spellings and the destruction and sacking of Rome and its churches over 1000 years. Virginia Ortenberg, a British historian, has even reconstructed a map of Rome at the time marking the churches visited. She has also managed to provide some valuable descriptions of the state of the churches at the time and major artwork, architectural features, tombs and reliquary within the church.

In an amazing feat of investigative academic research, there is almost universal consensus on the 23 churches noted in the diary of Sigeric’s visit to Rome, not a small task given the age of the document, the many possible interpretations that might have been given to some obvious mis-spellings and the destruction and sacking of Rome and its churches over 1000 years. Virginia Ortenberg, a British historian, has even reconstructed a map of Rome at the time marking the churches visited. She has also managed to provide some valuable descriptions of the state of the churches at the time and major artwork, architectural features, tombs and reliquary within the church. The diary is a small document; it immediately begins to record the return journey to Canterbury. The places named on the return journey are more open to debate and interpretation, Ortenberg has attempted to chart the pilgrimage home on a map. As noted, this one pilgrimage by Sigeric in 990 AD and the few pages of diary entries chronicling the stops on the return trip to Canterbury has become the wellspring of the Via Francigena, a route that has guided untold numbers of pilgrims to Rome for 1000 years.

The diary is a small document; it immediately begins to record the return journey to Canterbury. The places named on the return journey are more open to debate and interpretation, Ortenberg has attempted to chart the pilgrimage home on a map. As noted, this one pilgrimage by Sigeric in 990 AD and the few pages of diary entries chronicling the stops on the return trip to Canterbury has become the wellspring of the Via Francigena, a route that has guided untold numbers of pilgrims to Rome for 1000 years.

An hour or so later, I’ve managed to drop off all my meals, although once, I had one meal left over and had to figure out who I’d missed – a panic attack that I never wanted to repeat.

An hour or so later, I’ve managed to drop off all my meals, although once, I had one meal left over and had to figure out who I’d missed – a panic attack that I never wanted to repeat.

In the past few days, I experienced two events worth marking in time; I had my first haircut in over two months (sorry, photographic evidence will not be forthcoming) and I had my first sit-down coffee, a double espresso machiatto, in a proper glass cup in a new local coffee shop, one that will probably become my new home on Denman Street.

In the past few days, I experienced two events worth marking in time; I had my first haircut in over two months (sorry, photographic evidence will not be forthcoming) and I had my first sit-down coffee, a double espresso machiatto, in a proper glass cup in a new local coffee shop, one that will probably become my new home on Denman Street.  To be honest, even though we are only through phase one of what may be a long process, it hasn’t been that tough. So Far…

To be honest, even though we are only through phase one of what may be a long process, it hasn’t been that tough. So Far… I saw birds and beasts, a coyote, a woodpecker, a river otter, eagles, rabbits – all enjoying the quiet desolation resulting from our retreat from their habitat. Slowing down and mindfully observing has its benefits.

I saw birds and beasts, a coyote, a woodpecker, a river otter, eagles, rabbits – all enjoying the quiet desolation resulting from our retreat from their habitat. Slowing down and mindfully observing has its benefits.

I worked on jigsaw puzzles when I got to restless, unable to sit still anymore. It kept me from the Television and the train wreck south of the border that was so mesmerizing yet so demoralizing. Putting one piece in place gave me a sense of accomplishment, instant gratification and power in a new world where I had little of any of those feelings.

I worked on jigsaw puzzles when I got to restless, unable to sit still anymore. It kept me from the Television and the train wreck south of the border that was so mesmerizing yet so demoralizing. Putting one piece in place gave me a sense of accomplishment, instant gratification and power in a new world where I had little of any of those feelings.

Likewise for many friends spread outside my immediate neighbourhood, not forgotten and certainly not lost for anything more than the temporariness of the current construct.

Likewise for many friends spread outside my immediate neighbourhood, not forgotten and certainly not lost for anything more than the temporariness of the current construct.

Epictetus was a Roman Stoic philosopher whose teachings were preserved in two tracts called the Discourses and the Enchridion. It’s hard to miss the point:“…the gods have given us the most efficacious gift: the ability to make good use of our impressions.” …The knowledge of what is mine and what is not mine, what I can and cannot do. I must die. But must I die bawling? I must be put in chains – but moaning and groaning too? I must be exiled, but is there anything to keep me from going with a smile, calm and self-composed?” Discourses I.1

Epictetus was a Roman Stoic philosopher whose teachings were preserved in two tracts called the Discourses and the Enchridion. It’s hard to miss the point:“…the gods have given us the most efficacious gift: the ability to make good use of our impressions.” …The knowledge of what is mine and what is not mine, what I can and cannot do. I must die. But must I die bawling? I must be put in chains – but moaning and groaning too? I must be exiled, but is there anything to keep me from going with a smile, calm and self-composed?” Discourses I.1

Seneca is one of the three most famous Roman Stoics. His book, Letters from a Stoic, is required reading for anyone interested in this philosophic tradition. Seneca emphasized the capricious nature of Fortune; all that Fortune provides can be snatched away in an instant;

Seneca is one of the three most famous Roman Stoics. His book, Letters from a Stoic, is required reading for anyone interested in this philosophic tradition. Seneca emphasized the capricious nature of Fortune; all that Fortune provides can be snatched away in an instant;

I also avoid negative reinforcement, especially the aging male coffee clatch. They’re called ROMEOs – really old men eating out. I see them everywhere, befuddled anxious-looking men who gather at the corner cafe to read the newspapers together, express their shock and amazement at the current state of affairs in our city/province/nation/world, inevitably shining up the good-old-days, complete with our biases and privileges. It’s backward looking and hermetically sealed, dusty and dead, self fulfilling and incapable of admitting new experiences or insights.

I also avoid negative reinforcement, especially the aging male coffee clatch. They’re called ROMEOs – really old men eating out. I see them everywhere, befuddled anxious-looking men who gather at the corner cafe to read the newspapers together, express their shock and amazement at the current state of affairs in our city/province/nation/world, inevitably shining up the good-old-days, complete with our biases and privileges. It’s backward looking and hermetically sealed, dusty and dead, self fulfilling and incapable of admitting new experiences or insights. GLS is my latest antidote – my wonder drug – for staying open to the new; meeting head-on the uncertainty, change and unfamiliarity that comes with shaking up my deeply-held beliefs and challenging my preconceived notions.

GLS is my latest antidote – my wonder drug – for staying open to the new; meeting head-on the uncertainty, change and unfamiliarity that comes with shaking up my deeply-held beliefs and challenging my preconceived notions.  The other implicit factor in the rheostat model I have constructed is that reason controls passion.

The other implicit factor in the rheostat model I have constructed is that reason controls passion. The Autobiography of Red gripped me and discombobulated me in ways that I am still sorting through. It is complicated, inflammatory and rich with ambiguity, much of which I feel I’m missing. I need more – of something, I’m not sure what. Moving my rheostat isn’t helping much.

The Autobiography of Red gripped me and discombobulated me in ways that I am still sorting through. It is complicated, inflammatory and rich with ambiguity, much of which I feel I’m missing. I need more – of something, I’m not sure what. Moving my rheostat isn’t helping much. I’d written of my first – Aha – my teachable moment of experiencing Sappho rather than understanding her. My initial attempt to experience her poetry was to read everything in our assigned textbook, Stung with Love by Aaron Poochigian, before actually reading Sappho’s words. I was dialled in at about 90% reason on my reason/passion rheostat. I would find context and understanding through Poochigian before I read Sappho’s poems.

I’d written of my first – Aha – my teachable moment of experiencing Sappho rather than understanding her. My initial attempt to experience her poetry was to read everything in our assigned textbook, Stung with Love by Aaron Poochigian, before actually reading Sappho’s words. I was dialled in at about 90% reason on my reason/passion rheostat. I would find context and understanding through Poochigian before I read Sappho’s poems.  In contrast to Poochigian’s 50 dense pages of notes and explanatory miscellanea, Anne Carson’s introduction notes for If Not Winter are all of 5 pages long.

In contrast to Poochigian’s 50 dense pages of notes and explanatory miscellanea, Anne Carson’s introduction notes for If Not Winter are all of 5 pages long.  Eros the Bittersweet, one of Carson’s first books, published in 1986 reflects extensively on the elusive attraction of…well…attraction – Eros. It is no ordinary book; the Modern Library selected it to be one of the 100 best non-fiction books of all time.

Eros the Bittersweet, one of Carson’s first books, published in 1986 reflects extensively on the elusive attraction of…well…attraction – Eros. It is no ordinary book; the Modern Library selected it to be one of the 100 best non-fiction books of all time. Carson also brings her intellectual insight to bear on Plato’s discourse on Love and the challenges of the written word. She examines Phaedrus, Plato’s examination of love and his critique of writing.

Carson also brings her intellectual insight to bear on Plato’s discourse on Love and the challenges of the written word. She examines Phaedrus, Plato’s examination of love and his critique of writing.  My thoughts after each class are unpredictable, depending on whether I emerge confused or enlightened from the evening’s discussion.

My thoughts after each class are unpredictable, depending on whether I emerge confused or enlightened from the evening’s discussion. I also know that I resist; I resist new, I resist change and I resist that which makes me uncomfortable.

I also know that I resist; I resist new, I resist change and I resist that which makes me uncomfortable.  On September 4, I walked into the downtown campus of Simon Fraser University as a student, a real bona fide student. I had my own student card, I had a student account and a password that helped me navigate the labyrinth of rules and regulations guarding entrance to this august body.

On September 4, I walked into the downtown campus of Simon Fraser University as a student, a real bona fide student. I had my own student card, I had a student account and a password that helped me navigate the labyrinth of rules and regulations guarding entrance to this august body.  But first, a recap. Last year, I managed to stow away on a field trip organized by the Graduate Liberal Studies program at SFU. We spent three weeks in southern Spain, half doing it as a course for credit in the program, half as spouses of students, alumnae, itinerant vagabonds and other riff-raff. Truth be told, I was the only riff-raff.

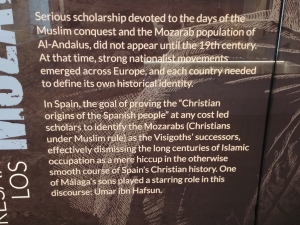

But first, a recap. Last year, I managed to stow away on a field trip organized by the Graduate Liberal Studies program at SFU. We spent three weeks in southern Spain, half doing it as a course for credit in the program, half as spouses of students, alumnae, itinerant vagabonds and other riff-raff. Truth be told, I was the only riff-raff.  The course was a study of the Islamic influence on Spanish culture; the Moors as they were called, ruled most of Spain from the 7th to the 14th century, in an uneasy relationship with the emerging Christian population and a significant Jewish community.

The course was a study of the Islamic influence on Spanish culture; the Moors as they were called, ruled most of Spain from the 7th to the 14th century, in an uneasy relationship with the emerging Christian population and a significant Jewish community. My week starts on Wednesday. I walk to the downtown campus for a 5pm dinner with my 15 classmates and our professor, Dr. Colby, for the first semester. The dinner is integral to the process, a freewheeling discussion o

My week starts on Wednesday. I walk to the downtown campus for a 5pm dinner with my 15 classmates and our professor, Dr. Colby, for the first semester. The dinner is integral to the process, a freewheeling discussion o At around 9:30 pm, I’m spun out into the street and off into the night. I wander home, dodging the nocturnals, most important of which are the skunks out foraging. I have to be careful because I’m in a bit of a state; the evening’s discussion can leave me gasping for air and feeling a little light-headed and therefore distracted, I need to remember to watch for the skunks. They do not like surprises!

At around 9:30 pm, I’m spun out into the street and off into the night. I wander home, dodging the nocturnals, most important of which are the skunks out foraging. I have to be careful because I’m in a bit of a state; the evening’s discussion can leave me gasping for air and feeling a little light-headed and therefore distracted, I need to remember to watch for the skunks. They do not like surprises! The requirements for the degree start with the two mandatory courses; Reason and Passion – I & II. The curriculum has been built, refined and tweaked over some twenty nine years by Dr. Stephen Duguid, the first Director; his stamp is still evident.

The requirements for the degree start with the two mandatory courses; Reason and Passion – I & II. The curriculum has been built, refined and tweaked over some twenty nine years by Dr. Stephen Duguid, the first Director; his stamp is still evident.  This semester our reading list ranges from Sappho, an enthralling Greek poet (her powerful words touch crusty old men across 2500 years of time), Plato (who knew he wrote important works other than the Republic?), Anne Carson (a Canadian, a McArthur fellow and author of a book designated as one of the 100 most important pieces of non-fiction of all time!), Virginia Woolf (I regret not having discovered her earlier in life, who knows how things might have been changed?) and Tompson Highway (another distinguished but often overlooked Canadian).

This semester our reading list ranges from Sappho, an enthralling Greek poet (her powerful words touch crusty old men across 2500 years of time), Plato (who knew he wrote important works other than the Republic?), Anne Carson (a Canadian, a McArthur fellow and author of a book designated as one of the 100 most important pieces of non-fiction of all time!), Virginia Woolf (I regret not having discovered her earlier in life, who knows how things might have been changed?) and Tompson Highway (another distinguished but often overlooked Canadian).

There is one other aspect to this decision to become a student.

There is one other aspect to this decision to become a student. Now, they’re not the big flashy high top ones that scared me when I first saw them, they were too much. But I have the iconic black lace-ups and I wear them to school every Wednesday night.

Now, they’re not the big flashy high top ones that scared me when I first saw them, they were too much. But I have the iconic black lace-ups and I wear them to school every Wednesday night.  Ten years ago, on June 29, 2009, I walked into Chef Patrice’s kitchen at Pacific Institute of Culinary Arts. I had just turned sixty and learning how to cook, really cook, seemed like a good idea; maybe a little late in the game but still full of possibility. Besides, it was my birthday present to myself.

Ten years ago, on June 29, 2009, I walked into Chef Patrice’s kitchen at Pacific Institute of Culinary Arts. I had just turned sixty and learning how to cook, really cook, seemed like a good idea; maybe a little late in the game but still full of possibility. Besides, it was my birthday present to myself. Chef Patrice, and later Chef Johannes, would become my kitchen gods; true chefs who had mastered the culinary skills, run successful restaurants, clawed their way to the top in a world where one bad review can destroy years of effort.

Chef Patrice, and later Chef Johannes, would become my kitchen gods; true chefs who had mastered the culinary skills, run successful restaurants, clawed their way to the top in a world where one bad review can destroy years of effort.  Our chef walked us through the basics of the French culinary tradition; knife skills, stocks and sauces, even a bit of baking. Our classroom was the kitchen; Chef demonstrated, we replicated – as best we could.